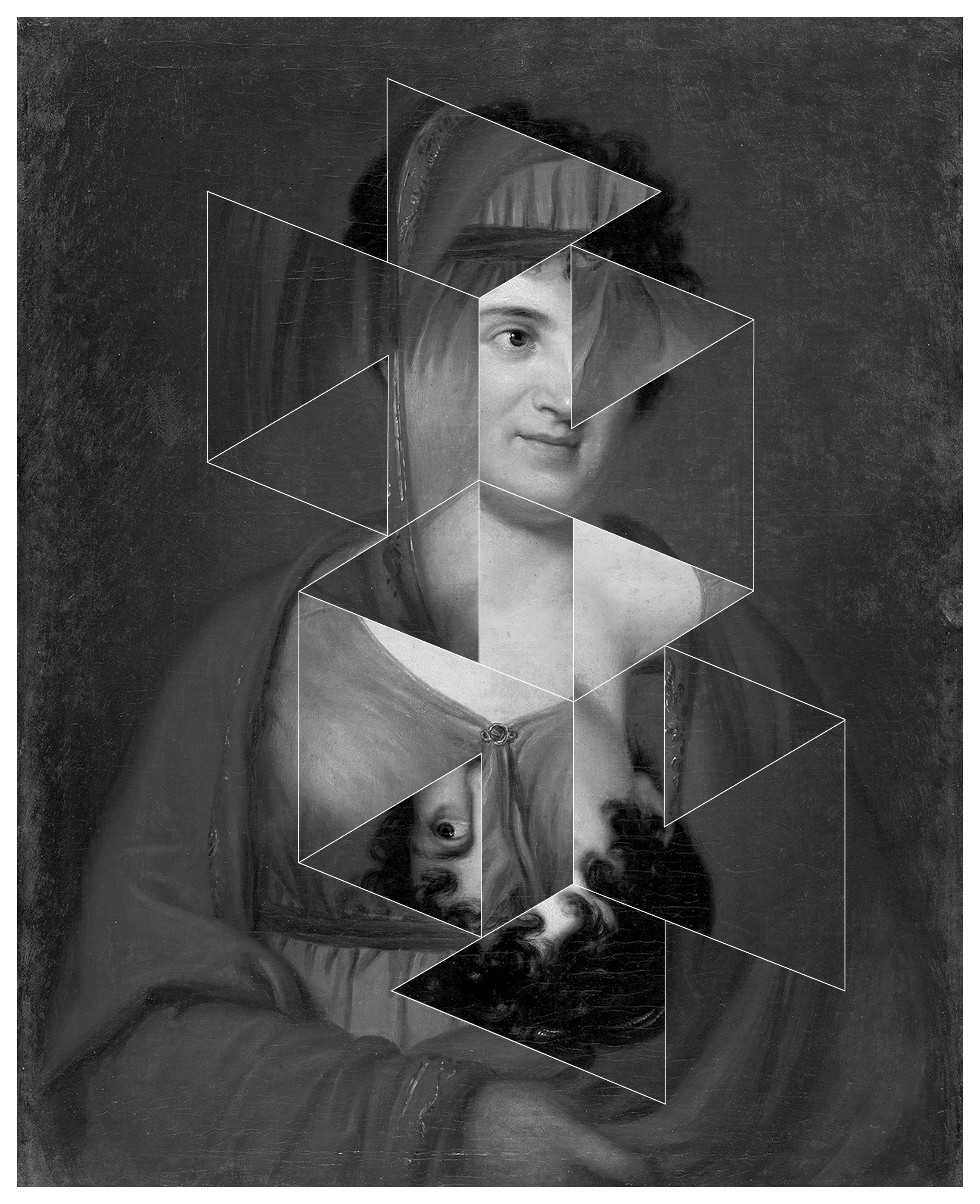

Henriette Herz (1764-1847) was best known for the literary salons that she started with a group of emancipated Jews in Prussia. She was the daughter of a physician, descended from a Portuguese Sephardic family of Hamburg. She grew up in Berlin and at fifteen married a doctor and philosopher, Markus Herz. The weekly gatherings at their house, eventually became structured into a science-seminar that was led by her husband to discuss scientific and philosophical questions of the enlightenment, and Herz’s literary salon which consisted of a younger crowd sharing poetry and prose. Some of their friends included sculptors, poets, authors, and theologians amongst others including Dorothea von Schlegel, Wilhelm von Humboldt, Jean Paul, Friedrich Schiller, Mirabeau, Shadow, Friedrich Schlegel, Friedrich Schleiermacher, and Alexander von Humboldt. The scholar and writer Karl Philip Moritz — a frequently attendee — introduced Goethe’s cult and German classical literature and neohumanism. This emphasis on a harmonious personality reached by the individual perfection of mind, soul and body. Herz provided an open environment to study such ideas supporting a free exchange of thoughts, ideas and knowledge about culture. She spoke many languages and was known to teach Hebrew lessons to some of the visitors which earned her the nicknamed, the “Salon Jewesses.”

After her husband’s death, and with the help from Schleiermacher, Herz converted to Protestantism. She refused to remarry and instead opened a private school for young women. Also, after her conversion, she was able to pursue her own wishes and spend time in Italy with close friends Dorothea Schlegel and Caroline von Humboldt. Already in her fifties, she started writing her autobiography when she was there. But instead of finishing it, she told her life story to Julius First, who wrote her memoir. Outside of this account Herz was thorough in burning her private correspondence and even went as far as to track down letters she sent to others. Few writings survived in various archives such as Karl Gustav Brinkmann’s, a diplomat of the Prussian court. Brinkmann was a close friend to Herz, bringing her books and tickets to the opera and theater when he visited her home every Friday evening for tea and conversation.

“The social, political and intellectual basis [ for salons such as Herz’s] was provided by enlightenment philosophy, augmented by poetical and philosophical emancipation of individual feeling. These social, not yet political ideals may be generalized as liberty, equality and fraternity. Just as philosophy, poetry and music united educated individuals from different religions, the salons of Jewish women formed a neutral, somewhat extraterritorial meeting ground for all those who wanted to bridge the gaps of rank in traditional Christian feudal society.” It is also important to acknowledge that most of the salons held in Berlin, were not about living a high-life, but about simplicity, genuine feelings, amusement and mutual education.

SOURCES

https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/berlin-salons-late-eighteenth-to-early-twentieth-century

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henriette_Herz

https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/herz-henriette